'It's the End of Days....'

- rabbirobynashworth

- Nov 10, 2024

- 7 min read

A sermon delivered at Birmingham Progressive Synagogue - 9 November 2024/8 Cheshvan 5785

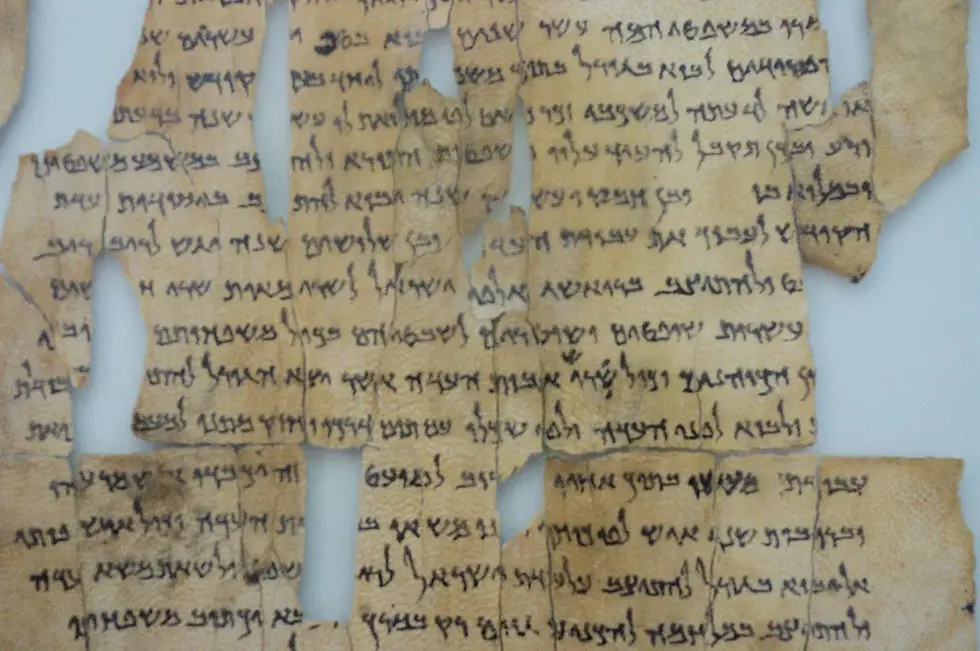

Maybe you have heard the story about one of the most exceptional archaeological finds in modern history. In the year 1947 three Bedouin shepherds came across jars in a cave near the Dead Sea. Within those jars lay 7 scrolls, preserved in the dry climate of the desert for many, many years. Over the next few years, despite politics and personalities, over 900 different manuscripts have been reconstructed from the various fragments found. This chance discovery was remarkable as scholars and practitioners now had texts that were some 1000 years older than any other biblical manuscripts until then. Through these fragments we have been able to learn more about the evolution of the Tanach, the Jewish sect that lived in these caves, and read material that, until the 1940s and 1950s was unknown. Indiana Jones - eat your heart out!

These are, of course, the Dead Sea Scrolls. And I encourage you, if you are interested, to look at the digital Dead Sea Scrolls library online and you can browse the various fragments and learn more.

Within the Dead Sea Scrolls, multiple copies were found of the Book of Jubilees. Known as a book within the collection named, Pseudepigrapha, a miscellaneous assortment of early Jewish and Christian writings. Now, the Book of Jubilees is not well known to us in Jewish communities. It’s not part of our sacred canon, and neither it is part of many Christian canons, though it is considered authoritative by the Ethiopian Church. Yet, this book is fascinating and well worth our attention.

The Book of Jubilees acts as a sort of early midrash, a commentary, upon Genesis and the early chapters of Exodus. The authors seek to provide colour and meaning to our early stories, to fill in gaps where things are not clear, and to add in some of their understanding of the world. In a time of division and empires they try to find a way through. The book presents itself in the voice of an Angel recounting these early stories to Moses. The authors add many details to the stories we know so well. For instance, our reading today in the Book of Genesis - Lech Lecha - begins with Avram hearing a divine call to leave his home. There is no build up to the story, before he hears the call we are just told, at the end of a long genealogy, that Avram was born and he then, with his family, settled in Haran. In the Jubilees story we are given much more detail. Think of it as a new film in a series (like Star Wars) which seeks to go back in time to explain the background to the now famous characters.

The Book of Jubilees tells us that Avram was already exceptional, before he receives the command to leave his home. He challenged his idol worshipping father, outwitting him and destroying his worthless idols. Avram then sat through the night to observe the stars and, as the text says, ‘a word came into his heart’. He prays to God to keep him from evil ways and, in response, he receives the call to leave. We hear, instead of Avram’s leaving straightaway, that he studies for 6 months! He then leaves with his father’s blessing. Quite a different to our story when we are provided with no context and no understanding of Avram’s mindset.

Even later we read of the Akedah, the near sacrifice of Isaac. Again the Book of Jubilees adds context and, much like the figure Job, we hear that an angel of darkness wants to test Abraham’s righteousness. God relents and it is not until a good angel (the narrator of the book) steps in to stay Abraham’s hand.

It is here that the Book of Jubilees becomes particularly interesting as it gives us an insight into how many Jewish sects in the Second Temple period understood the world to be made up of, not only hierarchies of divine beings, but that there were good and evil forces which worked against each other.

The sect of the Qumram community, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, called these forces the sons of light and the sons of darkness and they believed the end of days was coming and these forces would fight it out with the good being victorious and the righteous being rewarded. This type of theology seems quite far removed from the Judaism we practice today…or is it?

For the last few months, and beyond, particularly around the American election campaigning, these narratives of good versus evil have been resurfacing, across all of the political parties. And, with President Trump being re-elected, many have expressed that this is, in fact, the end of days. Similarly with the devastating conflict of Israel, Gaza and Lebanon, we have seen the same narratives within our communities as people are labelled ‘good’ Jews or ‘non-Jews’ depending on their political positioning - good or bad. The scenes we imbibe on a daily basis seem apocalyptic, just as the scenes painted in many of the manuscripts found at the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The narrative of good versus evil, culminating in the end of days, is terrifying. Yet, it is also strangely compelling as it provides supposed order and reason in a world of chaos and cruelty. There are those that are good - them - and there are those that are evil - us, and things will get better. It says ‘yes, everything feels dark now, but things will get better, you will be saved’ - ‘this darkness has meaning’ - it says. Yet, the relief this story provides is temporary and a fallacy. It is also very dangerous.

As I was getting the train earlier in the week, I overheard a commuter say to another person, unknown to her, that the people who voted in Trump were hateful. Hateful, evil, idiots, monsters. Of course, this narrative is compelling - it offers us hope in the face of suffering. But this narrative seeks to distance us from others who are not like us and provide a refuge of sorts as we hold onto our goodness and they, their wickedness. As we mark Remembrance weekend we are all too aware of how dangerous this trope is as sections of humanity are demonised - Jews as cunning, scheming creatures, Tuti Rwandans as cockroaches, migrants as swarms and so on.

In fact, our Haftarah portion today from Isaiah mirrors this narrative - violent scenes are depicted, the Israelites’ enemies will be taught a lesson, but they will be saved. We decided to read an alternative reading this Shabbat as it simply felt too painful to read today. Isaiah was a much loved prophet by the Qumram community and it makes sense as he promised salvation after a violent and bloody reckoning of righteousness versus wickedness.

Despite the popularity of this dualistic thinking - of evil forces versus good forces, rabbinic Judaism, eventually chose a different path. Indeed, a lot of texts are set up to reject the premise that there are evil forces apart from God. Instead, the rabbis chose, remarkably, debate and study in their times of crisis. They rejected a theology that rested upon a violent end of days but instead introduced the divine act of study.

There is one Talmudic story which drives this point home. We meet Reish Lakish - quite a character. Before he became an eminent rabbinic scholar he was a bandit and a gladiator. One day he came upon the beautiful Rabbi Yochanan and through his beauty and a promise of a wife, Resh Lakish returned to his learning. They became chevruta, study partners. They were inseparable. Yet, one day, during a discussion on the ritual impurity of weapons, Resh Lakish and Yochanan disagreed. Nothing new there. But Yochanan crossed a red line - he said to his friend, ‘well, you would know about weapons - a bandit knows about his banditry’. In that moment Yochanan labelled and othered his scholar friend. He dehumanised him and placed him in a lower category. A moment later we are told that Resh Lakish dies, so heinous was this moment. Yochanan was so distraught and could not be comforted. He too died.

This heartbreaking tale teaches us that rejecting someone’s humanity means that something in us dies. When we separate ourselves from the other and do not fully see them, when we do not sit with disagreement but lash out seeking a type of false, oppressive unity, we lose all that made us human.

The narratives of good versus evil, good people versus bandits, is destructive. Leaning into tropes that we are battling out these forces at the end of days may provide us with what feels like moral courage but, in the words of Brené Brown, who studies emotions, ‘we become the monster we wanted to kill.’ These narratives also take away our responsibility and power.

Indeed, in an article for the Guardian written by Aaron Glantz, a fellow at Stanford University’s Center for the Advanced Study of Behavioral Sciences, he states, ‘Trump’s victory is not the end of the world…we are the guardrails’. If we believe the end of the world is nigh, there is nothing else to work for. If we think we are battling evil forces who do bad things, we risk forgetting we are also capable of bad things, and cease to take care in what we do and what we say.

What we cannot do is meet our desperate need for hope and comfort by dehumanising others. Things are scary and there are people doing desperately bad things. We cannot give up hope but we also must not dehumanise, however right or tempting that feels. Resh Lakish, Yochanan, and so many others know the price this takes. Instead, what can we do? We come together, we pray, we study, and, through that strength we take action in whatever way we can. Crucially, we take action that affirms people’s humanity. Like the authors of the Book of Jubilees we choose to find meaning in a dark world, but we do so by recognising the beauty and complexity of humanity and hold onto our unique sacred nature.

Ken Yehi Ratzon - May this be so. Amen.

Comments